Brilliant @OSleisure and did u know National Parks were founded here in @peakdistrict with the Kinder Trepass https://t.co/D3GrPQdpqH

— Peak Chief Executive (@PeakChief) July 26, 2016

The Kinder Mass Trespass. It’s the most well known of all the protests in the rambling/outdoor movement – it’s possibly the ONLY well known aspect of the movement full stop. And therein lies the rub. As its centenary begins to approach (the event was 84 years ago now, in 1932), it’s status becomes ever more legendary. But are we celebrating the reality of the event, or a myth? The tweet quoted above, from the Peak District’s Chief Executive (who has been doing a great job in representing and promoting the Peak District), got me thinking about the debates about the event’s place in rambling history.

So first, some of the contentions any rambler will hear…

So first, some of the contentions any rambler will hear…

- The Kinder Mass Trespass was the first major protest in the rambling movement – MYTH! Many protests and trespasses had taken place in the 50 years before Kinder (1).

- The Kinder Mass Trespass was the largest major protest in the rambling movement – MYTH! Some protests, especially those in the North-West, attracted tens-of-thousands of protesters – and got quicker results too (2).

- The protest helped create or protect Public footpaths for us all to enjoy – MYTH! Public footpaths were already well-protected in law – the Kinder Mass Trespass was concerned with the Right to Roam over open countryside away from the footpaths.

- The protest helped create our National Parks – MYTH!

- The protest was a major step on the journey towards securing the Right to Roam? MTYH? Ah, well, here’s where it gets interesting!

The Kinder Mass Trespass is now well established in the public’s eye as THE major event in the rambling movement’s long fight to secure a Right to Roam (a fight that still isn’t fully won). Evidence of this can be seen even in information available on the Ramblers website repeating many of the myths above (read on to see why this is especially ironic!). However, once you dig deeper there is a lot more controversy surrounding the protest’s actual role in helping secure greater access.

The Case For

While the Kinder Mass Trespass was a long way from being the first or biggest such event, it probably can be credited with being the first to bring the issue of countryside access to a wider audience. Previous events had either been galvanising to local communities or to those campaigning for increased countryside access. Kinder changed that. This was arguably not through the effects of the trespass itself but through the official reaction to it, especially the harsh jail sentences handed out to the people involved.

The draconian punishments given to the ring leaders pushed countryside access into the national eye, far beyond its usual reach, helping creating a surge in interest. Although protests rallies had already been held at Winnat’s Pass (close to Kinder) for many years, the interest generated by the court cases saw crowds surge to over 10,000 in 1932. Many of the new attendees were reacting to what was seen as an example of a ruling class determined to stamp out any claim to the countryside by those in the industrial towns and cities.

The draconian punishments given to the ring leaders pushed countryside access into the national eye, far beyond its usual reach, helping creating a surge in interest. Although protests rallies had already been held at Winnat’s Pass (close to Kinder) for many years, the interest generated by the court cases saw crowds surge to over 10,000 in 1932. Many of the new attendees were reacting to what was seen as an example of a ruling class determined to stamp out any claim to the countryside by those in the industrial towns and cities.

Over the years the legend of the Kinder Mass Trespass grew, becoming the poster child for new generations of ramblers, angry with a lack of progress in achieving the aim of a Right to Roam. This is arguably the protest’s lasting legacy, providing a ‘foundation myth’ to spur on new protest movements throughout the 1900s. Although many of these movements never forgot the role of other protests, or the role of other organisations, in the access movement, the Kinder Mass Trespass was always the go-to event to help the public understand the context of their actions, especially in press reports.

The Case Against

At the time of the protest almost all the leading access campaigners of the day were against it. The Rambers Association, the Open Spaces Society, and leading campaigners such as Tom Stephenson all opposed the protest. Many other stalwarts of the rambling establishment were also critical, claiming the after-effects the protest would set the movement back by decades. Many people involved in the access movement had been attempting to engage with government and landowners to change the laws regarding access to open countryside, and were fearful that the protest would set this back. Some of the criticisms bordered on sour grapes, criticising the protest for not reaching the actual summit of Kinder for example. The leaders of the trespass were also criticised for being agitators, rather than ‘true believers’ in the countryside access cause, seeing it a convenient excuse to engage in a bit of a ruckus with those in authority.

At the time of the protest almost all the leading access campaigners of the day were against it. The Rambers Association, the Open Spaces Society, and leading campaigners such as Tom Stephenson all opposed the protest. Many other stalwarts of the rambling establishment were also critical, claiming the after-effects the protest would set the movement back by decades. Many people involved in the access movement had been attempting to engage with government and landowners to change the laws regarding access to open countryside, and were fearful that the protest would set this back. Some of the criticisms bordered on sour grapes, criticising the protest for not reaching the actual summit of Kinder for example. The leaders of the trespass were also criticised for being agitators, rather than ‘true believers’ in the countryside access cause, seeing it a convenient excuse to engage in a bit of a ruckus with those in authority.

These arguments against have created a powerful counter-argument to the more commonly understood narrative of the primacy of the Kinder trespass’ role in opening up the countryside.

Protest vs Dialogue

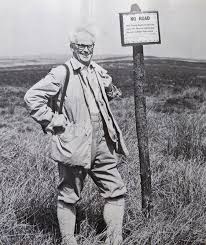

The disagreements over the impact and legacy of the Kinder Mass Trespass point to a wider debate regarding the best method of achieving change: a process of dialogue and engagement with authority, or one of actively rebelling against that authority. Tom Stephenson is the epitome of the dialogue approach. Over decades he worked tirelessly to campaign for the political change needed to open up the countryside. He led organisations like the Ramblers Association, and worked as a civil servant, drawing up plans for the Acts  of Parliament needed to turn the outdoor access movement’s aims into reality. Many of the things we take for granted in our countryside now come as a direct result of Tom Stephenson’s (and many other’s) work – in particular National Trails and our National Parks (3), but he was also a key player in the groundwork for defining the Access Land that was finally approved through Parliament in the Countryside & Rights of Way Act 2000, years after his passing. All involved in outdoor recreation owe Tom Stephenson a debt.

of Parliament needed to turn the outdoor access movement’s aims into reality. Many of the things we take for granted in our countryside now come as a direct result of Tom Stephenson’s (and many other’s) work – in particular National Trails and our National Parks (3), but he was also a key player in the groundwork for defining the Access Land that was finally approved through Parliament in the Countryside & Rights of Way Act 2000, years after his passing. All involved in outdoor recreation owe Tom Stephenson a debt.

However, it’s also true to say that protest also plays an active role in delivering change, one that is often under-recognised. For a start, as with the Kinder protest, it brings issues to a much wider audience than they might otherwise achieve. A mass trespass event will always be a greater hook for the press to turn into column inches than the efforts of a civil servant sitting in Westminster defining terms like ‘open countryside’, however vital their work was (and is). Protest can have a galvanising effect, making clear the injustice, and helping promote the cause outside of the narrow interest-groups who initially raise any specific issue. Between the two approaches there needs to be better recognition of the ways each has helped push forwards countryside access, and fewer attempts to play down the achievements of others.

It’s a touch ironic that many of the official organisations that decried the Kinder Mass Trespass originally are now some of the biggest cheerleaders for its recognition – as witnessed by the tweet quoted at the start of this blog. Many in the Open Spaces Society now admit they were ‘on the wrong side’ in relation to the event, National Trust have a ‘Trespass Trail’ available for download. The Ramblers, led by Tom Stephenson for many years, promotes the efforts to preserve the story of the trespass, crediting its role in creating the right to roam. Even the current Duke of Devonshire, whose moorlands the Kinder protestors were fighting to open, admitted at the 2002 anniversary rally to remember the Kinder trespass that his family were on the wrong side of history! A cynic might suggest this is, at least partly, a symptom of the commoditisation of history – the Kinder Mass Trespass sells! But it’s also a reflect that, after time passes it’s easier to see that the efforts of both protestor and peace-maker were both instrumental in the long battle for access to our countryside – a battle not yet fully won!

For my part, as much as I thank those in the trespass for the role they played in securing greater access, I hope people like Tom Stephenson aren’t forgotten.

Don’t forget about the birds?

Almost as a post-script to this blog, there is a current issue that shows the ‘protest vs dialogue’ debate is not only still live – but also still relevant to many of the concerns of the Kinder trespass: protecting/accessing our countryside, the actions of landowners and the Peak District landscape. A recent blog post from the ex-Peak District Chief Executive Jim Dixon picks up on the issues surrounding the campaign for greater protection for the Hen Harrier. The article hands out a severe admonishing to the wildlife campaigner Chris Packham for committing the crime of becoming too passionate about the plight of the Hen Harrier. Chris apparently allowed his passion to spill over into counter-productive anger. Instead of Chris attending events to raise awareness of the issue, it is proposed he simply needs to get out onto the moors and start talk to game keepers – that’s the way progress lies. Through cooperation, communication.

Almost as a post-script to this blog, there is a current issue that shows the ‘protest vs dialogue’ debate is not only still live – but also still relevant to many of the concerns of the Kinder trespass: protecting/accessing our countryside, the actions of landowners and the Peak District landscape. A recent blog post from the ex-Peak District Chief Executive Jim Dixon picks up on the issues surrounding the campaign for greater protection for the Hen Harrier. The article hands out a severe admonishing to the wildlife campaigner Chris Packham for committing the crime of becoming too passionate about the plight of the Hen Harrier. Chris apparently allowed his passion to spill over into counter-productive anger. Instead of Chris attending events to raise awareness of the issue, it is proposed he simply needs to get out onto the moors and start talk to game keepers – that’s the way progress lies. Through cooperation, communication.

Except, in many instances such an approach doesn’t work. Especially when it comes to Hen Harriers. For a few years campaigners have bemoaned the RSPB for precisely the opposite – for relying too much on cooperation and dialogue by taking part in the Government’s Hen Harrier Action Plan (the Hawk and Owl Trust have also been similarly criticised). However, after a sincere and committed attempt to work with this strategy, RSPB were left with no choice to pull out. You read more about why on Martin Harper’s blog post.

When the sheer determination of some stakeholders to resist change leads to organisations like as RSPB finding themselves unable to continue a dialogue the debate must be seen to be in a bad place. Such situations only serve to push ever larger groups to a more extreme, protest-based angle, as they see no other routes for meaning full progress. I hope, for the Hen Harrier’s benefit, some of the other key players, like the National Parks, DEFRA and others can see this and work positively. Rather than resorting to again distorting the debate by criticising campaigners who are starting to feel like all hope for a positive, consensus-based solution can work. With the Hen Harrier facing such a bleak future this is certainly this is an issue for anyone with a passion for our natural heritage to get involved in – regardless of whether your method of choice is protest or dialogue!

Footnotes / References

(1) & (2) As an example the Winter Hill Mass Trespass was earlier (1896), bigger (well over 10,000 people) and more successful than the Kinder trespass (at least in the short term)

(3) This is why my own hackles are raised by some of the mythology surrounding the Kinder Mass Trespass – not because I don’t recognise its role, but because I want to see the role of people like Tom Stephenson given more credit!

Picture references: Kinder Trespass plaque via libraryems on Flickr; Kinder Waymarker via Andrew Bowden on Flickr; Tom Stehenson via Tricouni Club; Pennine Way fingerbord via Andrew Bowden on Flickr; Hen Harrier via Rob Zweers on Flickr.

Some more reading on the Kinder Mass Trespass

Make up your own mind on the 1932 Kinder Mass Trespass with some of these sources!

- Tom Stephenson – Forbidden Land (Tom’s autobiography, essential reading for anyone interested in the history of the countryside access movement)

- Mike Parker – The Wild Rover

- Seven Blunders of the Peak (contains a chapter on the protest)

- Friends of the Kinder Trespass (great info on all sides of this debate)